[rating=4]Mary Bonnett’s “Invisible” is an extremely timely and thought-provoking tour de force. At the end of the show, a collective sigh can be heard from the audience—literally—just before the actors took their bows. It is the first time I’ve witnessed anything exactly like this! This was not a sigh of relief but that of recognition: History is repeating itself. Racial hatred and religious intolerance have reared their ugly head in America, just as they had done some 100 years ago.

[rating=4]Mary Bonnett’s “Invisible” is an extremely timely and thought-provoking tour de force. At the end of the show, a collective sigh can be heard from the audience—literally—just before the actors took their bows. It is the first time I’ve witnessed anything exactly like this! This was not a sigh of relief but that of recognition: History is repeating itself. Racial hatred and religious intolerance have reared their ugly head in America, just as they had done some 100 years ago.

“Invisible” depicts the Women’s Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) a little-known organization, stemming from the suffragists/suffragettes of the early 1920s. Once women were given the right to vote, they were empowered to exercise their muscle in the political realm. In the South, many turned to a nativist strain of patriotism: an offshoot of the white nationalist movement that disparaged blacks, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants, especially those from Eastern and Southern Europe. Although the WKKK was invisible at first, it soon became mainstream by forming social clubs and marching in public parades.

The dominant storyline of “Invisible” takes place in July 1925, in rural Mounds, Mississippi. Lucinda Davis (convincingly acted by Barbara Roeder Harris) and her daughter-in-law Doris Davis (Megan Kaminsky) are members of the local chapter of the WKKK who, together with Mabel Carson (Morgan Laurel Cohen) meet as a small group to strategize about how best to gather new recruits and organize their local chapter. Lucinda and Doris echo post-Civil War racism of the Deep South, whereas Mabel (who is originally from Missouri) is not as hard-core. Her husband Tom Carson (Brad Harbaugh) is from Mississippi and believes that Klan membership is good for his small business. As a consequence of an agile script, there are moments when the audience gets the unnerving feeling that they are actually a part of a WKKK rally. This is excellently done.

The second, and less obvious, storyline begins eleven years earlier, in 1914, and takes place adjacent to a Mississippi Indian mound. But first, some background.

Legend has it that on the banks of the Singing River in rural Mississippi, there once existed a tribe of light-complected American Indians who looked nothing like their kinsmen. The myth was that their ancestors had been born in the sea and had emerged onto the land. They were a gentle people with inspiring music, who worshipped a mermaid. They became known as the Pascagoula.

Around 1539, members of this peaceable tribe found themselves between a rock and hard place. The neighboring Biloxi Indians outnumbered the Pascagoula; and when a threatened intermarriage violated the peace agreement between them, this became a pretext for war. A year later, in 1540, when Hernando de Soto and the Spanish conquistadors were forcibly converting the “savage heathens” to Catholicism, the Pascagoula were being starved out by both of their enemies. Having no desire to change their religious beliefs and knowing that their fate was sealed, the entire tribe chose to drown themselves in the river—this after a bewitching mermaid rose up upon a giant column of waves to sing a soul-wrenching poem and entice the inhabitants into the churning waters.

As “Invisible” begins, Mabel’s profound grief for her deceased daughter Sarah stirs up the energies of the river, and one of the mermaid-like descendants of the Pascagoula tribe comes onto shore. Known throughout the play as “Ghost Girl” or “Alabaster” (and elegantly played by the precocious Maddy Fleming), she is given the name Dara by her adopted mother Jubilation Jones (Lisa McConnell), a multi-racial black woman and outcast from the dominant white society. In an era where race and color are king, the good-natured Jubel takes in Dara despite her porcelain/albino color, simply because she is a fellow human being. At first, Dara is a wild child, who is told on more than one occasion that she has a horrible odor (which alludes to the fact that she is still part sea-creature). But later, she takes a bath and puts on a new dress—and fully becomes flesh and blood. In so doing, she develops an acute awareness of the hatred around her and the cruelty that people can inflict on each other.

Inasmuch as Mabel tries to fit in with the other WKKK women and their politics, she fails to do so. She secretly embraces Dara, who sees ghosts and communicates with dead people, including Mabel’s deceased daughter Sarah. On occasion, Mabel associates with Jubel as well. While Jubel is powerless to fight back against the discrimination and bigotry in which she finds herself, Mabel is equally powerless to change things; for both are subject to the norms of a racist Southern culture. Mabel knows that there is more to life than the vitriol of hatred, but she goes along to get along and thus allies herself with whoever is in her presence. Although she lacks the inner fortitude to stand up for her opinions, this is out of a justifiable fear: She might be ridiculed at best, or beaten or killed at worst, if her true feelings were revealed. The Klan, she knows, is capable of doing anything in the name of the greater good. This conflict within Mabel’s character is interesting and thoughtfully developed.

However, this brings up a flaw in the script, namely, when commonplace reality collides with the metaphysical underpinnings of the characters of Jubel, Dara, and to a lesser extent, Mabel. To my taste, there is a bit too much fluidity between the various levels of reality, spirituality, and mysticism throughout the play. The good part about this fluidity is that this allows us to question the beliefs and suppositions that underlie our actions; namely, why, whether, and how we act on good and honest intentions, or not. The bad part about this fluidity is that commonplace reality ought to predominate throughout so that the horror of the WKKK is made more palpable.

However, this brings up a flaw in the script, namely, when commonplace reality collides with the metaphysical underpinnings of the characters of Jubel, Dara, and to a lesser extent, Mabel. To my taste, there is a bit too much fluidity between the various levels of reality, spirituality, and mysticism throughout the play. The good part about this fluidity is that this allows us to question the beliefs and suppositions that underlie our actions; namely, why, whether, and how we act on good and honest intentions, or not. The bad part about this fluidity is that commonplace reality ought to predominate throughout so that the horror of the WKKK is made more palpable.

The amalgamation of these two disparate storylines works smoothly on two occasions. The first is when a Jewish character, Mr. Stein (Richard Cotovsky) is severely beaten by the KKK for being Jewish and a newspaper reporter from the North, from Chicago no less. His wounds are treated by Jubel and Dara, who cannot understand the hatred against him. The second time is when Dara intervenes to prevent Mabel from being blackballed by the other WKKK members when they suspect that she has come from “too far north” and is really not “one of them” and is thus a threat to their community.

Towards the end, whatever excuse (or lack thereof) regarding Dara’s origins makes little or no sense and detracts from the main plot. Therefore, for the script to work well, it would be best to divorce the ghosts and the preternatural from the larger story and instead focus more on the political reality and the historical parallels with the present-day. Too much emphasis on bizarre family history dilutes from the shockingly harsh reality of Klan violence.

In spite of the ghastliness innate to the performance, death would have been better seen on stage rather than merely discussed.

Playwright Bonnett has done tremendous research for this production. I learned quite a lot about the WKKK and its propaganda from this performance, which spurred me to do some of my own research on the Klan. I discovered that there were actually two sequential KKK organizations. What was later to be called the “First Klan” was founded in 1865 to deprive African-Americans of their rights and newly-found freedoms at the end of the Civil War and throughout Reconstruction. Later, coincident with the movie “Birth of a Nation” in 1915, the Second Klan arose, together with full-blown nativism and anti-Jewish sentiment. Ironically, the founding of the ADL (Anti-Defamation League) of the B’nai B’rith and the revitalization of the KKK stemmed from the exact same event in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1913; namely, the imprisonment of Leo Frank, a Jew originally from Brooklyn, who was later killed by a lynch mob in 1915.

“Invisible” is about the invisible empire of the KKK, whose participants are shrouded in secrecy via their white robes. It is also about the invisibility of women, who briefly held political power but are later told by their fathers and husbands  that their participation is no longer needed in the political sphere—and that they are better off staying home to take care of kith and kin. Then too, there is the invisibility of persons of color in a racially charged society. Finally, it is a story about the invisible wings of a mysterious mermaid who is transformed into a human being during a troubled time period.

that their participation is no longer needed in the political sphere—and that they are better off staying home to take care of kith and kin. Then too, there is the invisibility of persons of color in a racially charged society. Finally, it is a story about the invisible wings of a mysterious mermaid who is transformed into a human being during a troubled time period.

I was honored to be in the audience last Sunday afternoon to watch “Invisible” and be a part of the poignant discussion that followed. Yet I am of two minds about the play itself. The performance is successful to the extent that we are willing to indulge the fantasy in addition to the history of the 1920s Klan. “Invisible” is thus a tale of two stories imperfectly meshed together, much like putting the wrong cover on a pot: It works well enough, but it could have been flawless.

This production of “Invisible” by Her Story Theater furthers its mission of being a “grass roots theater for social change….” Performances are at Stage 773, 1225 W. Belmont Avenue, Chicago, through November 3, 2019, according to the following schedule:

Thursdays through Saturdays – 7:30 p.m.

Sundays – 3:00 p.m.

Additional show on Saturday, November 2nd at 3:00 p.m.

For tickets, please contact: www.stage773.com/show/invisible

or phone the 773 box office: 773-327-5252.

For group ticket discounts, please call 312-835-1410.

More information on “Invisible” and Her Story Theater is available at www.herstorytheater.org

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Invisible”

More Stories

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone”

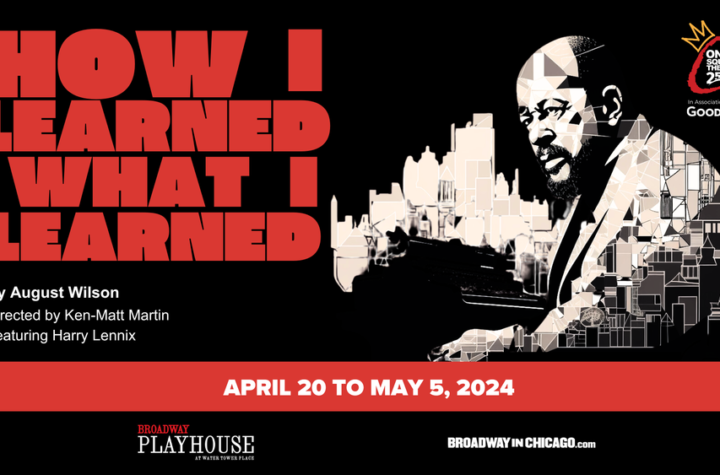

“How I Learned What I Learned” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Map” reviewed by Julia W. Rath