[rating=5]Since the 1970s, Nicholas Rudall has produced many engaging performances of classical drama at the University of Chicago’s Court Theatre. Since 1994, he has teamed up with Artistic Director Charles Newell with the aim of instilling a love of the classics among future generations of university students while making ancient works accessible to the public at-large.

[rating=5]Since the 1970s, Nicholas Rudall has produced many engaging performances of classical drama at the University of Chicago’s Court Theatre. Since 1994, he has teamed up with Artistic Director Charles Newell with the aim of instilling a love of the classics among future generations of university students while making ancient works accessible to the public at-large.

Sophocles “Oedipus Rex” (or “Oedipus the King”) has been a time-honored play that has persisted from Ancient Greek civilization into the present day. It has continually been revived and recast while staying true to its origins. What makes this production by the Court Theatre notable is that the original language has been modernized in Professor Rudall’s translation. Moreover, King Oedipus (Kelvin Roston, Jr.) and his daughter Antigone (Aerial Williams) are played by African-Americans. As Oedipus’s wife Queen Jocasta (Kate Collins) describes her deceased husband King Laius as being dark in physical appearance, making him African-American by implication adds a new dimension to the entire play.

As Oedipus gradually comes to understand that he was adopted by King Polybus and Queen Merope, of Corinth, he wonders who his birth parents are. Thus, he is placed in a predicament not unlike those of adopted children today, namely, wanting to know their true origins. The opening of adoption records over the last thirty or so years in the United States in combination with DNA testing have allowed many people to discover their identity and family history. After years of longing and curiosity, they can learn who their ancestors and birth parents are and whether they have siblings—and possibly why they may have been given up for adoption in the first place. While DNA has helped to resolve a lot of questions in the current day and age, Oedipus only had anecdotes, rumors, and gossip to guide him in his search.

While genetic testing has become of interest to everybody regardless of background or culture, it has gained particularly widespread appeal among African-Americans, whose families were often separated during the period of American slavery. Like Oedipus, they have been anxious to trace their roots through history. Hence, there is an additional nuance inherent to the performance when a black Oedipus wonders aloud whether he is a descendant of slaves or not.

Of course, we all know the basic story, where Oedipus kills his father and marries his mother, and so he is both son and husband to her. Such ugly secrets of murder and incest have been neatly concealed from him but are an abomination to the gods, who cast a plague on Thebes. The plague can only be lifted with the death of King Laius’s murderer, which (as time goes on) we discover to be in the person of Oedipus himself. When Jocasta figures all this out and realizes that she has been sleeping with her own son, she kills herself. In learning that he is a living abomination and has plunged his nation into ruin, he cannot live with himself. Whereas he earlier mocked the blind prophet, now Oedipus blinds himself. With this act of savagery, he cannot see with eyes anymore but now sees the truth. When Creon (Timothy Edward Kane), later takes over the throne, he proclaims that his brother-in-law has suffered enough and need not die (as the oracle of Apollo had originally commanded).

Roston does a phenomenal job as Oedipus, spellbinding us and energizing the action surrounding him. He ties the play together with his gripping performance. Chorus leader Mark Spates Smith ties things up differently: by singing a compelling song towards the end. His beautiful voice resonates throughout.

The technical achievements are perhaps the most extraordinary part of the production. The simple, stark yet effective stage design is the brainchild of John Culbert. Its minimalistic modernism features folding architecture in repeated patterns on the walls plus large steps and ample platforms, all in white, which resemble marble. Though columns and Greek keys are absent, the set allows us to conjure up an ancient palace in our imagination as well as visualize a world of gods and spirits (the Chorus) that underlies our material existence. The glaring light coming up through the set floor could easily represent the harsh reality of truth. Keith Parham, the lighting designer, is to be commended for his intermingling of lights of all types, colors, and brightness in keeping with the mystical revelations of the script. What a brilliant sensation he creates! On top of it all, white costumes, designed by Jacqueline Firkins, resemble shrouds as well as ancient Greek tunics; these add to the mystique in how they reflect the various lights on display. Oedipus’s purple robe demonstrates his wielding of regal power and influence. But as the king grows less and less certain of himself, his costume shifts to white, resembling that of a beggar. Sound design by Andre Pluess and Christopher M. LaPorte is equally spectacular with a series of sounds and music in perfect blend—full and balanced—using some of the most sophisticated computerized soundboards available.

The underlying question is this: whether Oedipus can be faulted for the circumstances of his birth and basically for situations beyond his control. The spirits behind the scenes adore his soul at conception. They hold it in a lighted sphere and display their love for an innocent child. But what if this baby boy is predestined to go out in society and do horrendous and shameful things as an adult?

Towards the beginning of the show, the gods and spirits welcome us into their deified world and serve as our guide to the action. The audience members become citizens of Thebes when the actors come through the aisles and greet all of us. But at the end of the day, it is we who serve as both judge and jury of this tale and its characters. It is we who establish where the lines are drawn as to whether an individual’s actions have been governed by their destiny or their free will. And it’s now your turn to take your place as a fellow citizen to serve in judgment. Court Theatre’s “Oedipus Rex” is beautifully executed and magnificently crafted. You too will decide that this amazing and thoughtful production should not be missed!

“Oedipus Rex” is playing at the Court Theatre, 5535 S Ellis Avenue, Chicago, through December 8, 2019.

Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays – 7:30 p.m.

Saturdays, Sundays – 2:00 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

There is no performance on Thursday, November 28th (Thanksgiving)

Note that the Saturday, November 30th 2:00 p.m. performance is audio-described for the visually-impaired and the Sunday, December 1st 2:00 p.m. performance is open-captioned for the hearing-impaired.

Ticket prices range from $35 to $80 and vary from performance to performance. Prices are subject to change.

Tickets are available through the box office at (773) 753-4472 or through courttheatre.org.

Court Theatre is located on the University of Chicago’s Hyde Park campus across the street from the Gerald Ratner Athletic Center and just south of the parking garage. Parking in the garage at the corner of 55th and Ellis is complimentary for Court Theatre patrons.

The #55 Garfield bus stops on 55th Street at S. Ellis Avenue. From the Loop, patrons can transfer from the Garfield Red Line train or the #6 Jackson Park Express.

For more information about the show and about parking, please contact the box office at (773) 753-4472 or via email at info@courttheatre.org.

To see what others are saying, visit http://www.theatreinchicago.com go to Review Round-Up and click at “Oedipus Rex”.

More Stories

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone”

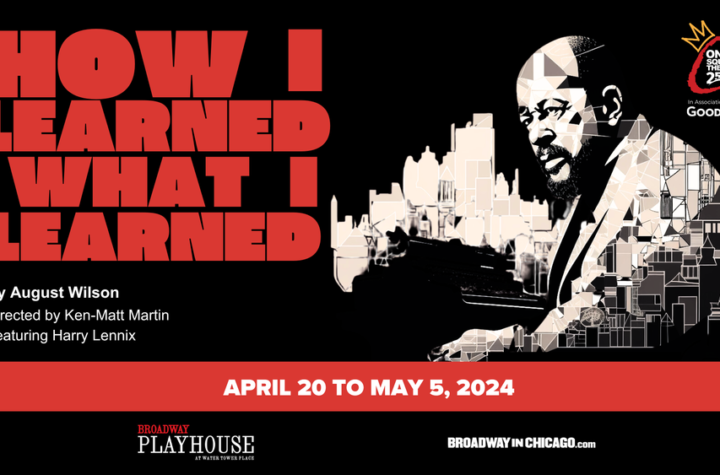

“How I Learned What I Learned” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Map” reviewed by Julia W. Rath