Recommended *** Part mystery, part contemporary history of a slice of the Jim Crow era, “Ohio State Murders” by Adrienne Kennedy is a play shrouded in a certain fatalism when the color line is breached. The performance informs us how race and racism dictated the spaces and places where blacks were allowed—or not allowed—to go in a northern State both in terms of physical location and “knowing your place” in the social order. This is a play not just of African American interest but is truly an American story, told from a perspective that many whites might not have considered: having to do with the racial divide in a city and on a campus where white people and white privilege dominated.

Recommended *** Part mystery, part contemporary history of a slice of the Jim Crow era, “Ohio State Murders” by Adrienne Kennedy is a play shrouded in a certain fatalism when the color line is breached. The performance informs us how race and racism dictated the spaces and places where blacks were allowed—or not allowed—to go in a northern State both in terms of physical location and “knowing your place” in the social order. This is a play not just of African American interest but is truly an American story, told from a perspective that many whites might not have considered: having to do with the racial divide in a city and on a campus where white people and white privilege dominated.

Suzanne (in a marvelous performance by Jacqueline Williams) fleshes out a distant memory when her much younger self (a young Suzanne, played by Eunice Woods) went to college at Ohio State University, in Columbus, Ohio. In 1950, Suzanne so desperately wanted to be an English major at a time when blacks were being held back from pursuing their aspirations. Because of university policy at the time, Suzanne was allowed to take only two classes in the English Department before she had to declare a major in English. But that major had to be approved—and for blacks, it never was. She was subsequently supposed to remain content taking trial courses in the subject. Yet there was one English professor Robert Hampshire, a/k/a Bobby (Shane Kenyon), who thought Suzanne was brilliant. He believed her analysis of a character’s thoughts and motivations in great literature was far above that of her peers and the other professors’ expectations. Due to circumstances that unfold during the course of the show, we learn that Suzanne had to constrain her ambitions and change her academic major to education, despite the fact that she didn’t find the subject matter challenging enough. We also learn that in later life, she became an acclaimed novelist who has typically incorporated violent plots in her books. But what was the origin of her writing about violence? She did not come from a violent household. Her detailed remembrance of the origins of the Ohio State murders is meant to serve as a catharsis for her, an explanation for her writings, and a revelation to the audience.

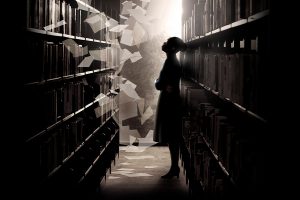

Thanks to director Tiffany Nichole Greene, the layering of Suzanne’s distressing reflections and flashbacks to the previous era is done seamlessly and brilliantly. It is a thrill to watch Suzanne and her younger counterpart frequently share frames throughout the retelling. The contemporary Suzanne often interacts with her previous self as a time traveler would: by remaining invisibly present. The intimacy of the camerawork in placing the two selves together and constantly separating them is amazing. As an example, I was so impressed with the 180-degree angle of the camera/switching when the tall library bookcase was placed between the older and younger characters: the bookcase being the original prop that begins the sequence of going back in time.

While this is a rather cerebral tale as it is currently being told, it didn’t have to be, nor should it have been. The rapport between the audience and Suzanne is excellent as long as the account remains largely psychological and the monologue internal. But the moment she relates too much of the action (as compared to just sharing her feelings about the action), the show stagnates. It becomes too much of a narrative rather than a whodunnit; and while that isn’t horrible, it could have been made substantially better. The problem is that the audience doesn’t see the murders with our own eyes, which would have added to the suspense. We beg to see an additional kind of flashback: one where the mystery truly comes alive before us and we are not told the outcome of the story. We deserve this, because especially in our modern era, we have seen so much cell phone video on our televisions and computer screens showing racially-tinged or racially-instigated killings live and in cold blood. Not seeing the whole truth depicted on stage detracts from the horrors of the lived and remembered experience by its very absence. The issue is not that of shock value: rather, a show about murders needs to stir up more visceral outrage. In brief, this presentation is too clean and too neat. Had we witnessed the spectacle for ourselves and its aftermath, the production would have earned a higher mark: The tenor of the script warrants it—and the sin and legacy of racism demands it.

The mobile cameras work well in creating this streaming video with their smooth movement from scene to scene, with the ever-so-slightly vibrating steadicams adding a simultaneous air of reality and unreality. Switching between the cameras is remarkably exact. Set design by Arnel Sancianco is smart: The sets portray both genuineness and minimalism, and their sequencing is superb. Lighting design by Jason Lynch works nicely, and sound design by Melanie Chen Cole is excellent. Costume design by Mieka Van Der Ploeg is authentic for the era. Supporting actors include: Dee Dee Batteast, Ernest Bentley, and Destini Huston, playing a host of different characters.

Murder can take place anywhere and to anyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, class, gender, or age. But when barely chronicled deaths of black people became normalized in the larger society and rarely discussed, this adds to the overall trauma and sense of loss. It is not necessarily in documented records or recordings where accounts of tragedy and violence reside, but in our memories. These memories can live deep within us and can influence our life course, even if the details may remain sketchy. Let us note on this Juneteenth weekend that grief multiplied by prejudice and hate may come out in distinct ways that may have a lasting impact. Yet whether we are a part of a marginalized group or not, we can all be affected by the pointless deaths of people in our community-at-large. Before we can say “Never forget”, we must first tell ourselves to remember the past and not discount our personal recollections of it.

“Ohio State Murders” is part of The Goodman Theatre’s “Live” Series, where live performances are being streamed on video in real time via their website: https://www.goodmantheatre.org/Live.

Individual tickets are $25. Experience this production and the next in the series with a Live Membership for just $40.

Remaining showtimes for the video stream are:

Saturday, June 19 – 2:00 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

Sunday, June 20 – 2:00 p.m.

To purchase tickets and for more information about “Ohio State Murders”, please visit: https://www.goodmantheatre.org/OhioState.

For more information about other shows or to donate to the Goodman Theatre, please go to: https://www.goodmantheatre.org/.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click “Ohio State Murders”.

More Stories

“How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Map” reviewed by Julia W. Rath

“Baby: the Musical”

“Nana” reviewed by Jacob Davis