[rating=5]Exceptional and poignant. “Rasheeda Speaking” is a four-person tragicomedy, with a well crafetd script written by the late Joel Drake Johnson. . The dialogue—sad, funny, and very real at the same time—is so well performed that you feel as if you could enter the stage yourself and interact with each of the characters in a real doctor’s office. Most of the time, we find ourselves not just watching a show but asking questions about each of the characters and their motives: “Who is lying?”, “Who is telling the truth?”, and, above all, “Who is Rasheeda?” Since the name makes its way into the title, you wonder when Rasheeda is going to speak to us and about what.

[rating=5]Exceptional and poignant. “Rasheeda Speaking” is a four-person tragicomedy, with a well crafetd script written by the late Joel Drake Johnson. . The dialogue—sad, funny, and very real at the same time—is so well performed that you feel as if you could enter the stage yourself and interact with each of the characters in a real doctor’s office. Most of the time, we find ourselves not just watching a show but asking questions about each of the characters and their motives: “Who is lying?”, “Who is telling the truth?”, and, above all, “Who is Rasheeda?” Since the name makes its way into the title, you wonder when Rasheeda is going to speak to us and about what.

This 95-minute one-act play, directed brilliantly by AmBer D. Montgomery, engages the audience’s attention throughout. It takes place at the office/reception area of Dr. Williams’ surgical practice, presumably located somewhere in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood. We never know why Dr. Williams (Drew Schad) hired Jaclyn (Deanna Reed-Foster) to work in his department in the first place, but we do know that she was promoted from the xerox department. Six months into the job, the doctor finds Jaclyn to be a disappointment for whatever reason, and he now wants to replace her with another employee. To facilitate Jaclyn’s termination, he enlists Ileen (Daria Harper), who has recently been promoted to office manager. He asks her to spy on Jaclyn and then hands her a little red notebook and asks her to document any and all of Jaclyn’s faults: every possible affront or issue, as trivial as it might be. And if there is nothing to write about, then Ileen is instructed to make something up.

Jaclyn suspects something is amiss when she returns to work after a five-day absence. It isn’t exactly clear whether she was out sick with a virus or an allergy or something else. But when the show opens, we learn that Jaclyn’s doctor has told her that she is allergic to a toxic environment. Therefore, Jaclyn surrounds herself with live green plants to clean out the air, and she also runs a fan on her desk. It turns out, however, that this is all a metaphor for the fact that the toxicity n the air is something that plants cannot remove; rather, it is the poison implicit in the personal relationships among the people working in the office. When patient meetings start taking place first thing in the morning without her, Jaclyn becomes clued in that her job may be on the line. But of course, nobody ever says what she might have done wrong. Hence, it becomes her guess (and the audience’s) as to whether the issue has something to do with her job performance—or something else, like racial prejudice, considering that she’s black and the rest of the office is white.

At the same time that she is spying on Jaclyn, Ileen tries hard to be the buffer between her and the doctor. But Ileen is caught in a no-win situation. She tries being friendly, but Jaclyn states things correctly: “We aren’t friends.” In fact, when Ileen tells Jaclyn to clean the floor and mop up some water, this could be taken as show of superiority, meant to humiliate Jaclyn, even if Ileen has meant it innocently in her new role as office supervisor.

I brought a guest with me who was in Human Resources Management (HR) to get her take on the show, and we agreed that since Jaclyn wanted to keep her job, she figured out how to adjust to circumstances. We both felt that the doctor and Ileen were judging her behavior at work against a set of white middle class social norms, and when Jaclyn adopted these norms and changed her behavior, she became more accepted in the office and also by the elderly patient Mrs. Sanders (Barbara Roeder Harris). But after this shared observation, my guest and I sharply differed in opinion: My guest felt that as time wore on, Jaclyn’s way of handling the job became more and more professional. In contrast, I saw nothing wrong at all with Jaclyn’s professionalism at the beginning of the show. She did her job the way she was told when it came to entering information and dealing with patients. But Jaclyn came from a different cultural background, where it was not required to socialize as being part of the job. To put this another way, the doctor and Ileen had both internalized the unconscious white middle class norm that it was important to become buddies with the staff in addition to doing their work; they believed that being superficially friendly was important to the job itself. Hence, they viewed Jaclyn’s not wanting to socialize as somehow being hostile and standoffish and thus undesirable.

Jaclyn, however, could see through all this. So when she makes the calculated decision to socialize (because she knows it’s expected of her), she intentionally plays games with everyone. For example, when she tells Ileen about the neighborhood she lives in—specifically, about the neighbor’s daughter who has gotten pregnant due to incest—she intentionally drops the girl’s age in every successive iteration of the story (from 15 down to 12) to add to the story’s shock value. Thus, she’s telling the people exactly what they have come to hear about the neighborhood she comes from. Whether any of this is true or not is another matter. Then too, she decides to give Ileen a gift to make up for her “bad behavior” (that is, her lack of friendliness), and the gift is supposed to be about how much their friendship means to each other. But we all know this is fake, and Jaclyn knows it’s a joke: that she’s playing Ilene. But Jaclyn is not the only one putting it on. We witness how every one of the characters has a false front; the exception being Mrs. Sanders, who says things how she sees them. Her comments lead to veiled and overt references about blacks and slavery that permeate this performance. Hence, there are warnings in the playbill and on site about the show possibly being offensive to some. They read: “Please note that ‘Rasheeda Speaking’ depicts sensitive content including but not limited to racial slurs, microaggressions, gaslighting, and respectability politics in the workplace.”

The stage is nicely turned into an office setting due to the efforts of scenic designer Scott Penner. Costume design by Rea Brown is perfectly appropriate for the setting. Jackie Fox’s lighting design is especially creative when you finally see Rasheeda! Christopher Kriz’s original music and sound design work well in this space, although I was concerned that people in the back row might not have been able to hear as well as they could. Persephone Lawrence’s props design is perfect for the setting. I especially liked the use of the three-hole punch, which is not as relevant today as in the recent past, since so much office work is being done on computers.

The show leads us to the question of whether there is an authentic black expression that ought to be recognized. But more to the point, if Jaclyn is “acting too white”, has she somehow sacrificed a part of herself? The wider question is whether anybody has an authentic personality, separate from the family or culture or neighborhood they grew up in or the larger culture that they may be a part of. Note that each and every one of us has to adjust to social norms at some level, regardless of our place in society. But in Jaclyn’s case, the question remains as to whether she is accepted by the world-at-large or not—or whether she will ever be accepted for the person she is. And who is this person? Is Rasheeda this authentic person—or is she a racial slur or a racial stereotype? Is she somebody to be praised or somebody to be feared or loathed? Then again, the show is full of racial and cultural assumptions that people make about each other and about themselves, having to do skin color or the neighborhood or background we may come from. It is this collision of cultures and styles that has to do with both the comedy and the tragedy inherent in this show. All this causes unease among members of the audience. When we don’t know when to laugh or how to react in general, that’s what makes this show so great. The combination of a fantastic script with marvelous acting makes this show a joy to watch. Perhaps it can help us to better recognize misunderstandings and underlying fears having to do with race and racism today. We can learn a lot about ourselves from this performance, and it’s well-worth seeing!

Shattered Globe Theatre’s production of “Rasheeda Speaking” is playing through June 4, 2022, at Theater Wit, at 1229 W Belmont, Chicago, between Southport and Racine Avenues.

General admission tickets are $45.

General admission tickets are $45.

$15 for students

$35 for seniors

$25 for those under 25 years old

Performance schedule:

Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays – 8:00 p.m.

Sundays – 3:00 p.m.

No performance on Thursday, May 19, 2022.

Additional performance: Saturday, June 4, 2022 – 3:00 p.m.

A post show discussion immediately follows the Sunday, May 22nd show.

Note that some live performances can also be accessed online for remote viewing.

These take place: on May 26, 27, 28, and 29. For more information, contact the box office in person or by calling 773-975-8150.

Tickets are available via https://sgtheatre.org/, by calling 773-975-8150, in person at the Theater Wit Box Office, or by going to: https://www.theaterwit.org/tickets/productions/445/performances#top.

For more information about the show, go to: https://sgtheatre.org/rasheedaspeaking/.

For general information about Shattered Globe Theatre and to find out about their other offerings, visit: https://sgtheatre.org/.

Everyone is required to be vaccinated for COVID to enter the Theater Wit, and each audience member must show proof of vaccination and state ID at the door on arrival. Negative PCR and rapid test results are not valid for admittance. If you forget proof of vaccination, the theater will reschedule your tickets at no charge. There are also free exchanges due to illness.

Masks are required for this performance.

To see what others are saying, visit www.theatreinchicago.com, go to Review Round-Up and click at “Rasheeda Speaking”.

More Stories

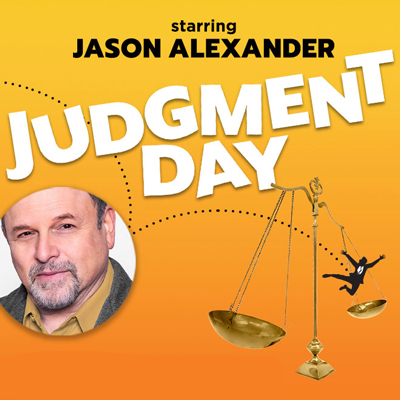

“Judgement Day”

“Bluey’s Big Play” reviewed by Tommaso Casati

“Beautiful: The Carole King Musical”